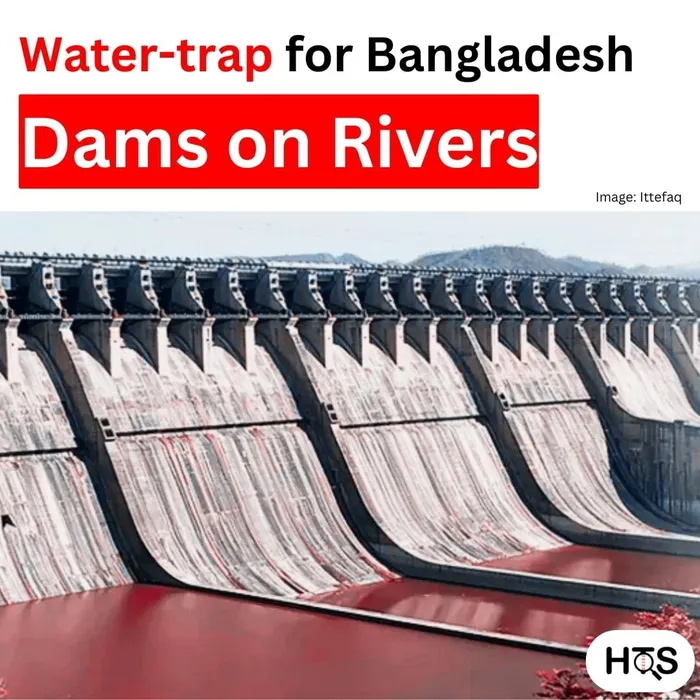

Dams on Rivers: Water-trap for Bangladesh

A dam is essentially a structure that blocks or regulates the flow of water, forming an artificial reservoir. This reservoir can then be utilized for various purposes, such as providing irrigation to agricultural lands or supplying drinking water to communities both nearby and at a distance. Dams are also vital in the generation of hydroelectric power, harnessing the energy of flowing water to produce electricity. Additionally, they serve an important function in flood management by preventing or reducing the risk of flooding in vulnerable areas.

However, the process of constructing a dam is not simply a matter of selecting a site and building it. The development of dams is often subject to a complex web of international laws and bilateral agreements, particularly when the dam affects watercourses that traverse or border multiple countries. These legal frameworks are designed to ensure that the interests of all parties are considered, and that the construction and operation of the dam do not cause harm to neighboring nations or regions that rely on the shared water resources.

Legal Aspects

The International Watercourses Convention, adopted in 1997 and becoming legally binding on August 17, 2014, establishes crucial guidelines for the management and use of water from rivers that cross or define borders between countries. The convention’s primary focus is on ensuring that water resources are utilized in a manner that is fair and sustainable, especially when the rivers flow from upstream to downstream nations.

Under this legal framework, it is prohibited for any country to construct a dam or undertake any activity that could negatively impact a neighboring state by altering the river’s natural flow. Such actions could have serious consequences, including environmental degradation, disruption of water supplies, and harm to local communities and economies in downstream areas. To prevent these issues, the convention requires that countries take into account the potential effects of their actions on other nations sharing the river (as per the Article 7 of the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention).

Moreover, the convention imposes specific obligations in times of emergency. If an upstream country needs to open the gates of a dam, it is legally required to notify downstream nations in advance. This ensures that downstream countries have the opportunity to prepare and mitigate any potential risks, such as flooding or sudden changes in water availability (as per the Article 12 of the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention).

Article 5 of the convention emphasizes the principle of equitable and reasonable use of water resources. This means that countries sharing a transboundary or international river must cooperate to ensure that each nation receives a fair share of the benefits while also taking on a fair share of the responsibilities. This cooperative approach is essential for maintaining peaceful and sustainable management of shared water resources.

Context: Bangladesh

Countries worldwide respect international norms to ensure the proper management of shared rivers, recognizing that cooperation and equitable resource sharing are essential for regional stability, environmental sustainability, and the well-being of the populations that rely on these water resources. For instance, the Danube River, which flows through 12 countries in Central and Eastern Europe, is a prime example of successful transboundary water management. The Danube River supports the development of beautiful cities, including three capitals—Vienna, Budapest, and Belgrade—along its banks. This cooperative management fosters economic growth, cultural exchange, and environmental protection, benefiting all nations involved.

That’s how it should be, right? But the situation is quite different for Bangladesh, a riverine nation with a landscape interwoven by 54 rivers that flow from neighboring India. As a downstream nation, Bangladesh faces a tough reality—India has constructed dams and barrages on every single one of these rivers, significantly impacting the natural flow and availability of water in Bangladesh.

Despite being a “friendly” neighbor, India has often been slow or reluctant to finalize fair water-sharing treaties, leaving Bangladesh to grapple with the consequences. The construction of these dams has led to reduced water flow during the dry season, affecting agriculture, fisheries, and the overall ecology of the regions dependent on these rivers. Furthermore, during the monsoon season, the sudden release of water from these dams can cause devastating floods in downstream areas, exacerbating the vulnerability of communities living along the riverbanks.

This situation puts Bangladesh in a precarious position. The country’s economy, food security, and environment are heavily dependent on the consistent and fair flow of water from these transboundary rivers. The lack of comprehensive and binding agreements on water sharing between Bangladesh and India highlights the challenges that smaller, downstream nations often face in negotiating with larger, upstream countries.

The inequitable water distribution and the absence of timely agreements strain the relationship between the two countries and raise concerns about long-term regional stability. While international norms and conventions emphasize cooperation and equitable sharing of transboundary water resources, the on-ground reality for Bangladesh reflects a significant disparity in power and influence, where the rights and needs of downstream nations are often overshadowed by the interests of their more powerful upstream neighbors.

Rights or Charity?

The issue of water-sharing between Bangladesh and India has been a long-standing and contentious matter, particularly concerning the Teesta River, one of the most critical transboundary rivers for Bangladesh. While there is an existing treaty for the Ganges River, the situation remains unresolved for eight other major rivers, including the Teesta. These rivers are vital for Bangladesh’s agriculture, livelihoods, and overall ecosystem, making the lack of formal agreements a significant concern for the country.

Historical Context and the Ganges Treaty

The Ganges Water Sharing Treaty, signed in 1996, marked a significant achievement in bilateral relations between Bangladesh and India, providing a framework for water distribution during the dry season. However, this treaty covers only one of the 54 rivers shared by the two countries, leaving many other important rivers, like the Teesta, without similar agreements.

The Teesta River Dispute

Discussions over the Teesta’s water sharing have been ongoing for decades, with the river being a critical lifeline for millions in northern Bangladesh. The Teesta supports vast agricultural activities in the region, and its water is essential for irrigation, especially during the dry season. However, the flow of the river has been a point of contention, with Bangladesh often receiving a significantly reduced share of water due to upstream diversions in India.

The 1983 Ad-Hoc Agreement

In 1983, an ad-hoc agreement was signed between Bangladesh and India to share the Teesta’s waters, allocating 39% of the flow to India, 36% to Bangladesh, and leaving the remaining 25% unallocated. However, this agreement was only a temporary measure and expired after six years in 1989, leaving the issue unresolved and leading to years of negotiation without a permanent solution.

The 2011 Near Agreement

In 2011, there was a significant development when a new water-sharing agreement for the Teesta was almost finalized. The agreement was expected to be signed during Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s visit to Bangladesh on September 6, 2011. However, the deal was abruptly halted when Mamata Banerjee, the Chief Minister of West Bengal, refused to endorse the agreement and canceled her visit to Dhaka. Her opposition stemmed from concerns that the proposed sharing formula would disproportionately affect West Bengal’s water needs.

Mamata Banerjee’s decision led Prime Minister Manmohan Singh to refrain from signing the deal without her approval, as water-sharing agreements in India often require the consent of affected state governments. This unexpected turn of events left the Teesta agreement in limbo, despite the significant diplomatic efforts that had gone into its formulation.

Recent Developments and Continued Stalemate

Even during the last term of the Awami League government in Bangladesh, there were efforts to finalize the Teesta agreement. The deal was reportedly ready, but once again, the signing never took place, highlighting the complexities and sensitivities involved in transboundary water-sharing agreements. The lack of progress on the Teesta agreement continues to be a major point of contention in Bangladesh-India relations, with Bangladesh facing significant challenges in managing its water resources effectively without a formal agreement.

Broader Implications

The unresolved status of the Teesta and other rivers underscores the broader difficulties in negotiating transboundary water-sharing agreements, particularly when the interests of upstream and downstream countries diverge. For Bangladesh, the delayed agreements and unfulfilled promises exacerbate concerns over water security, agricultural sustainability, and the overall well-being of millions who depend on these rivers.

The situation also reflects the complex interplay between central and state governments in India, where regional politics can significantly influence international agreements. In the case of the Teesta, West Bengal’s concerns have been a major barrier to reaching a consensus, despite the broader diplomatic relations between the two nations.

The unresolved issue of water-sharing, particularly concerning the Teesta River, remains a significant challenge in Bangladesh-India relations. While the Ganges Treaty offers a precedent for cooperation, the failure to finalize agreements on other important rivers highlights the need for continued dialogue, mutual understanding, and political will from both sides. For Bangladesh, securing a fair and equitable share of transboundary waters is crucial for its agricultural sector, ecological balance, and the livelihoods of millions of its citizens.

The management of transboundary rivers between Bangladesh and India has long been a source of tension, with accusations of exploitation and unfair practices exacerbating the situation. In addition to stalling water-sharing agreements, India has faced criticism for unauthorized water extraction from several border rivers, further straining the delicate balance of resources shared between the two countries.

One striking example of this exploitation is the situation with the Feni River, which flows from the Indian state of Tripura into Bangladesh. Over the years, India has installed 36 pumps upstream on the Feni River, extracting significant amounts of water without adequate consultation or agreement with Bangladesh. Despite the existence of the Joint Rivers Commission, established in 1972 to address such issues, there has been little to no enforcement of regulations regarding these extractions, leaving Bangladesh at a severe disadvantage.

The impact of this unauthorized water extraction has been devastating. Over the past 20 years, the water flow in the Feni River has decreased by nearly 60%. This reduction in flow has had a ripple effect, contributing to the decline of the river’s ecological health and severely affecting the livelihoods of communities dependent on the river for agriculture, fishing, and daily water needs. The Feni River, like many others in Bangladesh, is now on the brink of death, with its reduced flow leading to severe navigability issues and threatening the region’s agricultural productivity.

The situation with the Feni River is not an isolated case. Many of Bangladesh’s rivers are facing similar fates, as upstream water management practices in India have led to drastic reductions in water flow. The construction of dams, barrages, and unauthorized water extraction points upstream has left many rivers in Bangladesh struggling to maintain their natural flow, leading to a cascade of environmental and economic consequences.

As a downstream nation, Bangladesh is particularly vulnerable to these changes. Reduced river flows have led to increased sedimentation, shrinking river channels, and the drying up of wetlands and floodplains. These changes exacerbate the risks of droughts during the dry season and devastating floods during the monsoon season, as the country struggles to manage the altered water regimes. The loss of navigability in these rivers also impacts trade and transportation, further hampering the economic development of the affected regions.

Joint Rivers Commission

The Joint Rivers Commission (JRC) was established in 1972 with the goal of addressing water-sharing issues between Bangladesh and India and fostering cooperation over the management of shared rivers. However, despite its long-standing existence, the JRC has often been criticized for its ineffectiveness in resolving key disputes and ensuring equitable water distribution.

One of the main challenges facing the JRC is the power imbalance between the two countries. Bangladesh, as a smaller and downstream nation, often finds itself in a more vulnerable position in negotiations. India’s greater political and economic power has led to a situation where Bangladesh’s concerns are sometimes overlooked or inadequately addressed. The perceived submissive stance of Bangladesh towards India in these negotiations has left its people increasingly vulnerable to the consequences of unequal water management, including droughts, floods, and the loss of vital resources.

The continued exploitation of Bangladesh’s rivers threatens not only the environment but also the livelihoods of millions of people who depend on these waters. Without fair and cooperative management of these shared resources, the future of many of Bangladesh’s rivers—and the communities they support—remains in jeopardy. It is crucial for both Bangladesh and India to work together to find sustainable solutions that ensure the long-term health and viability of these transboundary rivers, fostering a relationship built on mutual respect and shared responsibility.

The consequences of inadequate water management and weak foreign policy have become increasingly evident in Bangladesh, where the actions of a neighboring country have led to devastating impacts on agriculture, livelihoods, and the overall economy. This “neighbor-made disaster” is not only harming crops and displacing people but is also directly slowing down economic growth in a nation that heavily depends on its rivers.

Impact

Agriculture is the backbone of Bangladesh’s economy, employing nearly half of the population and contributing significantly to the country’s GDP. However, the erratic and often manipulated water flow from upstream dams in India has made agricultural activities increasingly precarious. The Teesta River, which is vital for irrigating vast swathes of farmland in northern Bangladesh, has been severely affected by India’s Teesta Barrage. During the dry season, the dam drastically reduces water flow, leading to drought conditions that leave crops parched and fields barren. Conversely, during the monsoon, the sudden release of water from the dam can cause widespread flooding, washing away crops and devastating entire farming communities.

This situation is mirrored in other parts of the country, most notably in the western regions affected by the Farakka Barrage on the Ganges River. The barrage, designed to divert water to the Indian state of West Bengal, has long been a source of contention. It exacerbates drought conditions in Bangladesh during the dry season, reducing water availability for irrigation and drinking. During the rainy season, when excess water is released, the barrage contributes to severe flooding, displacing thousands and destroying homes, infrastructure, and farmland.

The human cost of this water mismanagement is staggering. In border areas such as Comilla, Sylhet, Feni, and Noakhali, the opening of upstream dams frequently results in floods that submerge entire villages, forcing people to flee their homes. These floods not only cause immediate suffering but also have long-term effects, such as the loss of arable land due to erosion, the destruction of crops, and the spread of waterborne diseases. The displacement of people and the destruction of livelihoods strain the social fabric of affected communities and place additional burdens on an already fragile economy.

The economic impact extends beyond agriculture. The frequent occurrence of floods and droughts disrupts transportation, trade, and industrial activities, leading to significant financial losses. The costs of disaster response, rehabilitation, and rebuilding are substantial, diverting resources away from other critical areas of development. Over time, these recurrent disasters erode the economic gains made by the country, slowing down overall progress and exacerbating poverty in the affected regions.

The Role of Foreign Policy and the Joint Rivers Commission

The ongoing crisis highlights a broader issue: the price of incompetence in managing foreign relations and water resources. For the past decade and a half, Bangladesh’s foreign policy towards India regarding transboundary water issues has been criticized for its weakness and lack of assertiveness. The Joint Rivers Commission, established in 1972 to address these very issues, has been largely ineffective in securing fair and equitable agreements that protect Bangladesh’s interests. The commission has failed to prevent the frequent occurrences of floods and droughts, leaving Bangladesh vulnerable to the actions of its more powerful neighbor.

This ineffectiveness has had dire consequences. The lack of a comprehensive and enforceable water-sharing agreement for rivers like the Teesta has allowed India to prioritize its own needs at the expense of downstream Bangladesh. The repeated delays and failures to sign agreements, despite extensive negotiations, underscore the challenges Bangladesh faces in protecting its water rights and ensuring a stable and sustainable future for its people.

The current situation is unsustainable and demands urgent action. Bangladesh must strengthen its foreign policy to more effectively advocate for its rights and interests in transboundary water management. This includes revitalizing the Joint Rivers Commission, pushing for the enforcement of existing agreements, and seeking new, binding treaties that ensure equitable water sharing. Furthermore, Bangladesh should engage with international bodies to garner support and pressure for fair resolutions.

The price of incompetence is too high to ignore. The ongoing disaster, driven by upstream actions, is crippling Bangladesh’s agriculture, displacing its people, and stalling its economy. To secure a prosperous future, it is imperative for Bangladesh to take a firmer stance in negotiations, protect its rivers, and safeguard the livelihoods of millions who depend on these vital resources.

The Ganges Water Sharing Treaty between Bangladesh and India has faced criticism for irregular implementation, with Bangladesh often receiving less water than agreed. Beyond the Ganges, India’s exploitation of other shared rivers has severely impacted Bangladesh, turning it from a river-rich nation into one with dying rivers. This has harmed agriculture, drinking water supplies, and the environment. The Indian government’s refusal to equitably share water is viewed as an unacceptable denial of Bangladesh’s rightful access to these resources, underscoring the need for stronger diplomatic efforts and international support to secure fair water-sharing agreements.